|

|

For anyone who is unaware, the title of the article echoes a 1953 Nature paper [1], which was instead “of considerable biological interest” [2]

|

|

Introduction

I have been very much focussing on the start of a data journey in a series of recent articles about Data Strategy [3]. Here I shift attention to a later stage of the journey [4] and attempt to answer the question: “How best to deliver information to an organisation in a manner that will encourage people to use it?” There are several activities that need to come together here: requirements gathering that is centred on teasing out the critical business questions to be answered, data repository [5] design and the overall approach to education and communication [6]. However, I want to focus on a further pillar in the edifice of easily accessible and comprehensible Insight and Information, a Structured Reporting Framework.

In my experience, Structured Reporting Frameworks are much misunderstood. It is sometimes assumed that they are a shiny, expensive and inconsequential trinket. Some espouse the opinion that the term is synonymous with Dashboards. Others claim that that immense effort is required to create one. I have even heard people suggesting that good training materials are an alternative to such a framework. In actual fact, for a greenfield site, a Structured Reporting Framework should mostly be a byproduct of taking a best practice approach to delivering data capabilities. Even for brownfield sites, layering at least a decent approximation to a Structured Reporting Framework over existing data assets should not be a prohibitively lengthy or costly exercise if approached in the right way.

But I am getting ahead of myself, what exactly is a Structured Reporting Framework? Let’s answer this question by telling a story, well actually two stories…

The New Job

Chapter One

In which we are introduced to Jane and she makes a surprising discovery.

Jane woke up. It was good to be alive. The sun was shining, the birds were singing and she had achieved one of her lifetime goals only three brief months earlier. Yes Jane was now the Chief Executive Officer of a major organisation: Jane Doe, CEO – how that ran off the tongue. Today was going to be a good day. Later she kissed her husband and one-year-old goodbye: “have a lovely day with Daddy, little boy!”, parcelled her six-year-old into the car and dropped her off at school, before heading into work. It was early January and, on the drive in, Jane thought about the poor accountants who had had a truncated Christmas break while they wrestled the annual accounts into submission. She must remember to write an email thanking them all for their hard work. As she swept into the staff car park and slotted into the closest bay to the entrance – that phrase again: “Jane Doe, CEO” in shiny black letters above her space – she felt a warm glow of pride and satisfaction.

Jane sunk into the padded leather chair in her spacious corner office, flipped open her MacBook Air and saw a note from her CFO. As she clicked, thoughts of pleasant meetings with investors crossed her mind. Thoughts of basking in the sort of market-beating results that the company had always posted. And then she read the mail…

… unprecedented deterioration in sales …

… many customers switched to a competitor …

… prices collapsed precipitously …

… costs escalated in Q4, the reasons are unclear …

… unexpected increase in bad debts …

… massive loss …

… capital erosion …

… issues are likely to continue and maybe increase …

… if nothing changes, potential bankruptcy …

… sorry Jane, nobody saw this coming!

Shaken, Jane wondered whether at least one person had seen this coming, her predecessor as CEO who had been so keen to take early retirement. Was there some insight as to the state of the business that he had been privy to and hidden from his fellow executives? There had been no sign, but maybe his gut had told him that bad things were coming.

Pushing such unhelpful thoughts aside, Jane began to ask herself more practical questions. How was she going to face the investors, and the employees? What was she going to do? And, she decided most pertinent of all, what exactly just happened and why?

In an Alternative Reality

Chapter One′

In which we have already met Jane and there are precious few surprises.

|

|

Jane did some stuff before arriving at work which I won’t bore the reader with unnecessarily again. Cut to Jane opening an email from her CFO…

|

|

… it’s not great, profit is down 10% …

… but our customer retention strategy is starting to work …

… we have been able to set a floor on prices …

… the early Q4 blip in expenses is now under control …

… I’m still worried about The Netherlands …

… but we are doing better than the competition …

… at least we saw this coming last year and acted!

Jane opened up her personal dashboard, which already showed the headline figures the CFO had been citing. She clicked a filter and the display changed to show the Netherlands operations. Still glancing at the charts and numbers, she dialled Amsterdam.

“Hi Luuk, I hope you had a good break.”

“Sure Jane, how about you?”

“Good Luuk, good thank you. How about you catch me up on how things are going?”

“Of course Jane, let me pull up the numbers… Now we both know that the turnaround has been poorer here than elsewhere. Let me show you what we think is the issue and explain what we are doing. If you can split the profit and loss figures by product first and order by ascending profit.”

“OK Luuk, I’ve done that.”

“Great. Now it’s obvious that a chunk of the losses, indeed virtually all of them, are to do with our Widget Q range. I’m sure you knew that anyway, but now let’s focus on Widget Q and break it down by territory. It’s pretty clear that the Rotterdam area is where we have a problem.”

“I see that Luuk, I did some work on these numbers myself over the weekend. What else can you tell me?”

“Well, hopefully I can provide some local colour Jane. Let’s look at the actual sales and then filter these by channel. Do you see what I see?”

“I do Luuk, what is driving this problem in sales via franchises?”

“Well, in my review of November, I mentioned a start-up competitor in the Widget Q sector. If you recall, they had launched an app for franchises which helps them to run their businesses and also makes it easy to order Widget Q equivalents from their catalogue. Well, I must admit that I didn’t envisage it having this level of impact. But at least we can see what is happening.

The app is damaging us, but it’s still early days and I believe we have a narrow window within which we can respond. When I discussed these same figures with my sales team earlier, they came up with what I think is a sound strategy to counterpunch.

Let me take you through what they suggested and link it back to these figures…”

The call with Luuk had assured Jane that the Netherlands would soon be back on track. She reflected that it was going to be tough to present the annual report to investors, but at least the early warning systems had worked. She had begun to see the problems start to build up in her previous role as EVP of UK and Ireland, not only in her figures, but in those of her counterparts around the world. Jane and her predecessor had jointly developed an evidence-based plan to address the emerging threats. The old CEO had retired, secure in the knowledge that Jane had the tools to manage what otherwise might have become a crisis. He also knew that, with Jane’s help, he had acted early and acted decisively.

Jane thought about how clear discussions about unambiguous figures had helped to implement the defensive strategy, calibrate it for local markets and allowed her and her team to track progress. She could only imagine what things would have been like if everybody was not using the same figures to flag potential problems, diagnose them, come up with solutions and test that the response was working. She shuddered to think how differently things might have gone without these tools…

The lie through which we tell the truth [7]

I know, I know! Don’t worry, I’m not going to give up my day job and instead focus on writing the next great British novel [8]. Equally I have no plans to author a scientific paper on Schrödinger’s Profitability, no matter how tempting. It may burst the bubble of those who have been marvelling at the depth of my creative skills, but in fact neither of the above stories are really entirely fictional. Instead they are based on my first hand experience of how access to timely, accurate and pertinent information and insight can be the difference between organisational failure and organisational success. The way that Jane and her old boss were able to identify issues and formulate a strategic response is a characteristic of a Structured Reporting Framework. The way that Jane and Luuk were able to discuss identical figures and to drill into the detail behind them is another such characteristic. Structured Reporting Frameworks are about making sure that everyone in an organisation uses the same figures and ensuring that these figures are easy to find and easy to understand.

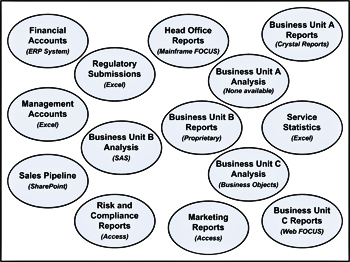

To show how this works, let’s consider a schematic [9]:

A Structured Reporting Framework leads people logically and seamlessly from a high-level perspective of performance to more granular information exposing what factors are driving this performance. This functionality is canonically delivered by a series of tailored dashboards, each supported by lower-level dashboards, analysis facilities and reports (the last of which should be limited in number).

Busy Executives and Managers have their information needs best served via visual exhibits that are focussed on their areas of priority and highlight things that are of specific concern to them. Some charts or tables may be replicated across a number of dashboards, but others with be specific to a particular area of the business. If further attention is necessary (e.g. an indicator turns red) dashboard users should have the ability to investigate the causes themselves, if necessary drilling through to detailed transactional information. Symmetrically, more junior staff, engaged in the day-to-day operation of the organisation, need up-to-date (often real-time) information relating to their area, but may also need to set this within a broader business context. This means accessing more general exhibits. For example moving from a list of recent transactions to an historical perspective of the last two years.

Importantly, when a CEO like Jane Doe drills through from their dashboard all the way to a list report this would be the identical report with the identical figures as used by front-line staff day-to-day. When Jane picks up the ‘phone to ask a question of someone, regardless of whether they are a Country Manager, or an operations person, the figures that both see will be the same.

When not accessed from dashboards, reports and analysis facilities should be grouped into a simple menu hierarchy that allows users to navigate with ease and find what they need without having to trail through 30 reports, each with cryptic titles. As mentioned above, there should be a limited number of highly functional / customisable reports and analysis facilities, each of whose purpose is crystal clear.

The way that this consistency of figures is achieved is by all elements of the Structured Reporting Framework drawing their data from the same data repositories. In a modern Data Architecture, this tends to mean two repositories, an Analytical one delivering insight and an Operational one delivering information; these would obviously be linked to each other as well.

Banishing some Misconceptions

I started by saying that some people make the mistake of thinking that a Structured Reporting Framework is an optional extra in a modern data landscape. In fact is is the crucial final link between an organisation’s data and the people who need to use it. In many ways how people experience data capabilities will be determined by this final link. Without paying attention to this, your shiny warehouse or data lake will be a technological curiosity, not an indispensable business tool. When the sadly common refrain of “we built state-of-the-art data capabilities, why is noone using them?” is heard, the lack of a Structured Reporting Framework is often the root cause of poor user adoption.

When building a data architecture from scratch, elements of your data repository should be so aligned with business needs that overlaying them with a Structured Reporting Framework should be a relatively easy task. But even an older and more fragmented data landscape can be improved at minimal cost by better organising current reports into more user-friendly menus [10] and by introducing some dashboards as alternative access points to them. Work is clearly required to do this, which might include some tweaks to the underlying repositories, but this is does not normally require re-writing all reports again from scratch. Such work can be approached pragmatically and incrementally, perhaps revamping reports for a given function, such as sales, before moving on to the next area. This way business value is also drip fed to the organisation.

I hope that this article will encourage some people to look at the idea of Structured Reporting Frameworks again. My experience is that attention paid to this concept can reap great returns at costs that can be much lower than you might expect.

It is worth thinking hard about which version of Jane Doe, CEO you want to be: the one in the dark reacting too late to events, or the one benefiting from the illumination provided by a Structured Reporting Framework.

If you would like to learn more about the impact that a Structured Reporting Framework can have on your organisation, or want to understand how to implement one, then you can get in contact via the form provided. You can also speak to us on +44 (0) 20 8895 6826.

Notes

[1] |

WATSON, J., CRICK, F. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature 171, 737–738 (1953). |

[2] |

From what I have gleaned from those who knew (know in Watson’s case) the pair, neither was (is) the most modest of men. I therefore ascribe this not insubstantial understatement to either the editors at Nature or common-all-garden litotes. |

[3] |

All of which are handily collected into our Data Strategy Hub. |

[4] |

Though not necessarily much later if you adopt an incremental approach to the delivery of Data Capabilities. |

[5] |

Be that Curated Data Lake or Conformed Data Warehouse. |

[6] |

See the Cultural Transformation section of my repository of Keynote Articles. |

[7] |

Albert Camus, referring to fiction in L’Étranger. |

[8] |

I still have my work cut out to finish my factual book, Glimpses of Symmetry. |

[9] |

This is a simplified version of one that I use in my own data consulting work. |

[10] |

Ideally rationalising and standardising look and feel and terminology at the same time. |

Another article from peterjamesthomas.com. The home of The Data and Analytics Dictionary, The Anatomy of a Data Function and A Brief History of Databases.

Like this:

Like Loading...

A skilled practitioner, hard at work developing elements of a Structured Reporting Framework

A skilled practitioner, hard at work developing elements of a Structured Reporting Framework ©

©

!["Users are the root of all evil" - anonymous [failed] BI Project Manager "Users are the root of all evil" - anonymous [failed] BI Project Manager](https://i0.wp.com/peterjamesthomas.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/down-with-users.jpg?resize=200%2C288)

You must be logged in to post a comment.